Police Emergency Squad

It is not how they died, but how they lived – a quote seen so many times, in so many contexts, that its origin is lost. But it is difficult to find a better example to showcase this ideal than that of Captain John C. Loran, Louisville Police Department

Although Emergency Medical Services, known for short as EMS, is the youngster in the public safety field, the need for emergency medical assistance has always existed. In the distant past, such assistance was provided by the true first responders, friends and family, or bystanders, or the first arriving emergency responder, law enforcement or firefighters. But in the early years of the 20th century, Louisville law enforcement took a huge leap by creating an emergency squad specifically trained to respond to medical emergencies.

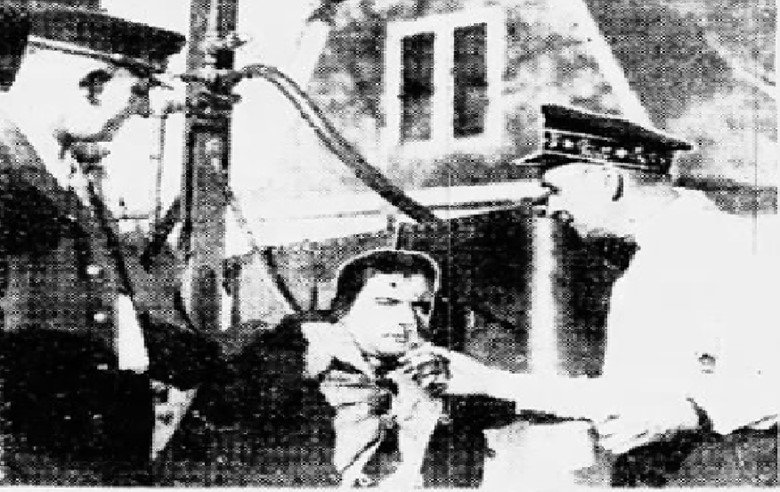

On August 11, 1936, Captain John C. Loran, Louisville Police Department, died of typhoid fever at the age of 61. He was stricken with symptoms first in his office at the Second District on August 4 and taken to his modest home at 2737 Alford Avenue and from there, rushed to the Methodist Episcopal Deaconess Hospital at 529 South Eighth Street. It is, of course, impossible to say this was what would now be recognized as a line of duty death, because there is no way to know now how he contracted this deadly disease. The newspaper reported that during his final hours, the same emergency squad he had founded, instructed and headed worked hard to administer oxygen in an effort to save his life.

Just months before, in December, 1935, he had been voted the “most valuable Louisville policeman” by the 400-odd members of the Louisville Police Department in a secret ballot. On January 1, 1936, Safety Director Dunlap Wakefield awarded him a gold medal. Before he joined the police department on November 18, 1918, Loran had for 12 years served as a private detective for the Haager-Donohue Detective Agency. He had previously been the U.S. Navy, during the Spanish-American War, served as a fireman and locomotive engineer for the Louisville & Nashville Railroad and even, during the World War, was with the Secret Service. Once sworn in, he was soon made a desk sergeant, then a “roundsman,” and moving quickly through the ranks of lieutenant and captain. He was described as an “even-tempered, gentle officer who could be unexpectedly hard when necessary.” He was mild-mannered with the small offenders and tough with the “designing criminal.”

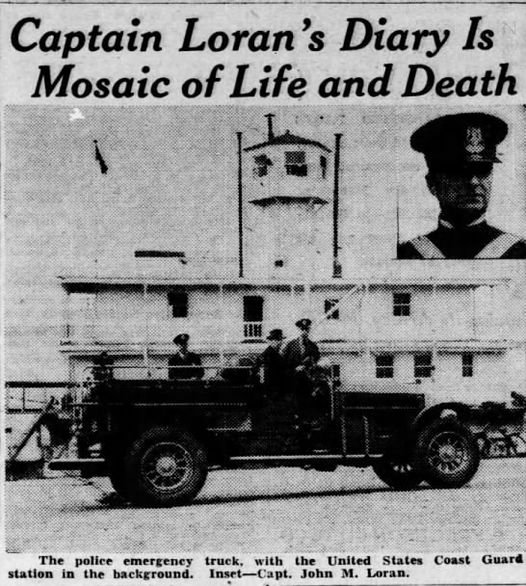

As a lieutenant, Loran became the first head of the traffic bureau, created by Chief Forrest Braden in 1920. Seeing another need, he pleaded, cajoled and beggared for the creation of an emergency rescue service, which was first outfitted with a “few odds and ends of rescue equipment” and forced to depend upon a police patrol unit to rush him, and his skeleton crew, to accident scenes. A few years later, he was provided with a truck that was equipped with a few necessities, and he, along with his men, are estimated to have responded to close to 3,000 rescue runs. His small squad never failed to respond to extra alarm fire calls, drowning calls or other accidents, often being called even with off duty. Doctors who received an emergency call to assist at home, contacted Captain Loran if artificial respiration might be required, and would even follow the speeding red truck to the scene.

He also oversaw traffic regulation, and handled parades for any number of celebrities at the time, including three presidents (Harding, Hoover and Franklin Roosevelt) and as well as presidential candidates.

Captain Loran kept a daybook and its last entry was the day before he took ill, August 3. It showed that over his career, he saved, or participated in saving, 397 lives. That National Safety Council awarded him in 1923 for saving four lives in a single month. Loran served as a speaker at the first annual police training school, sponsored under the Kentucky Municipal League at the University of Kentucky in 1935, with his topic being First Aid. In a show of mutual aid, Captain John Loran was stationed at the gate of My Old Kentucky Home in Bardstown with the duty to admit only those with a proper invitation card to the grounds during the visit of Queen Marie of Romania during her 1926.

Captain Loran’s daybook (actually three cloth and leatherbound books) was showcased in a 1934 article in The Courier-Journal. It was described as a “mosaic of life and death, of comedy and tragedy and of hope and despair.” Although his entries were terse, they laid out what he (and by extension, the traffic bureau and the rescue squad) had done every day. Two entries for February 7, 1931, showed how, like police work now, a day could go from tragedy, a teenager overcome and dying by gas while bathing in his home to a toddler, choking on a peanut, who survived by the same technique we would recognize today. Day by day, the diary recorded trauma, heart attacks, drownings, asphyxiations, burns, electrical shocks, gas and carbon monoxide fumes. He stated that fires and explosions were the worst, as there would be so many casualties, and the very worst of those he recalled was the January 6, 1930, Mengel Body Company fire at Thirteenth and Dumesnil streets. There, one firefighter was killed and 45 injured. Another remembered fire was the burning of the Woolworth 5&10 in downtown Louisville, in March, 1921, when scores were overcome by fumes from the burning celluloids. No one died at that fire although a firefighter did die months later, and his death was attributed to the gas masks the department had just started to use at that fire, when they were found to be flawed. On Ohio River drownings, they would be augmented by the U.S. Coast Guard, with the Guard handling the recovery and the squad handling resuscitation efforts. He emphasized how he never gave up until he was certain the victim was gone.

As Captain Loran was in failing health by the end of 1935, he was relieved of the responsibility of the traffic bureau in early 1936 and was assigned less physically demanding duties, supervising initially the Third District, and then the Second District headquartered in City Hall. There he stayed until August, 1936.

At Loran’s funeral, scores of people passed through his home, where he was laid out, to pay their respects. Many were individuals whose lives he had saved, including a Miss Dorothy Meyer, age 15, who had been badly injured in a car crash eight years before. Captain Loran had labored tirelessly to save her life with the pulmotor and oxygen. Fire Captain William H. Kramer, who had twice been revived by Captain Loran at fire scenes, stopped by as well.

Loran’s final service was held from the Grace Lutheran Church on North 26th street and his body was taken there early for visitors as well. He is buried in Cave Hill Cemetery. His active and honorary pallbearers included fellow Louisville Police Department officers, along with members of the Fire Department, the Coast Guard and ambulance attendants.

Safety Director Wakefield stated:

"Louisville, and particularly the Division of Police, have suffered an irreparable loss. Instances of such prolonged devotion to a public service ideal are rare. Captain Loran’s honesty and genial personality had endeared him to thousands."

Captain John M. Moran was survived by his wife, Florence, born Mayer, who followed him in death in 1983, two daughters, Evelyn and Naomi and three sons, Leslie, Robert and William. At his wife’s death, she was buried in Resthaven and her obituary indicated that she was survived by two of her three sons, Leslie having predeceased her, and her daughters, and had 11 grandchildren, 19 great-grandchildren and even a great-great grandchild. She remained a member of the Retired Police Officers and Widows Association.